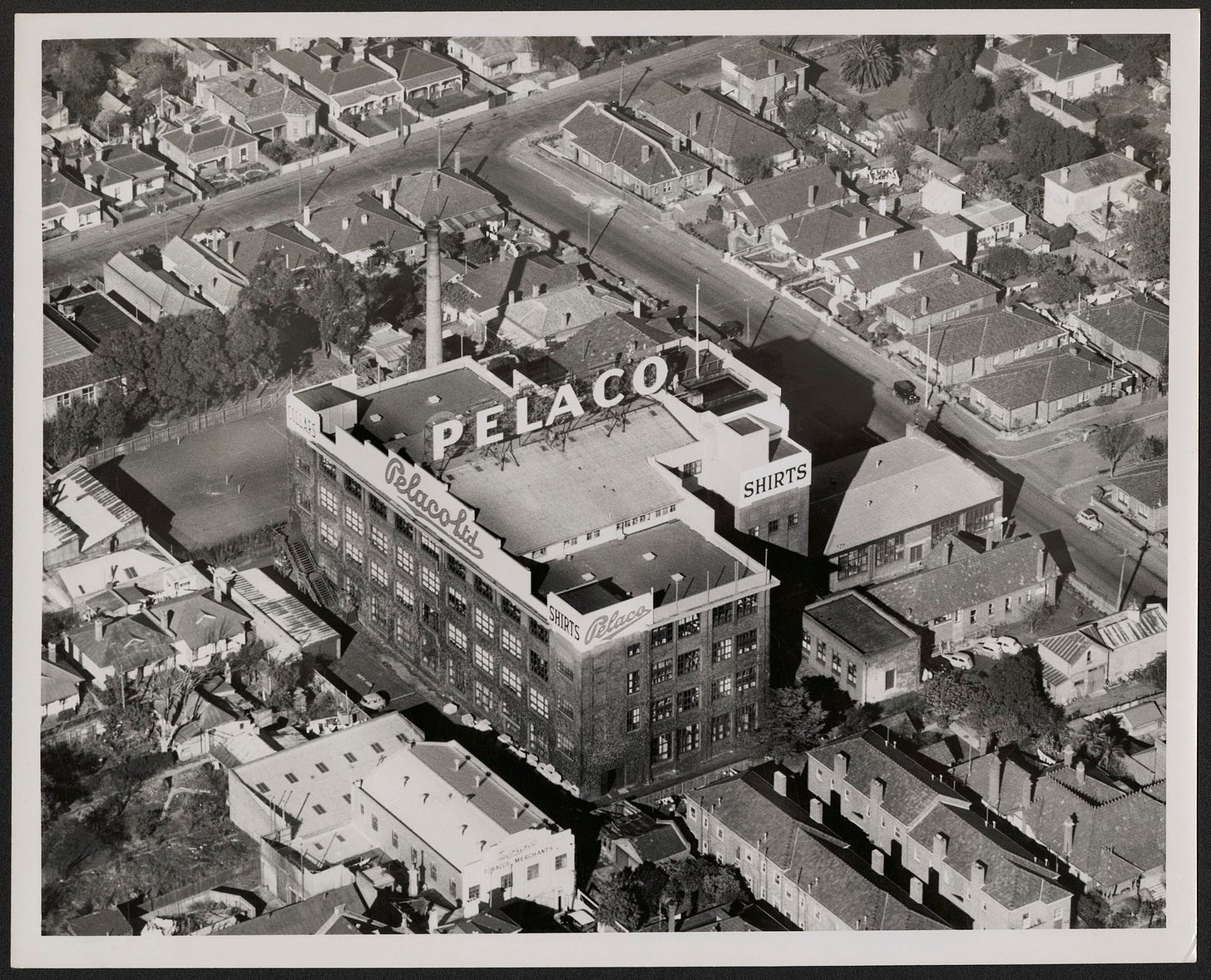

The PELACO sign. Five hulking letters perched high on Richmond Hill like a neon tombstone for Melbourne’s former manufacturing might. Once it glowed like a branding iron of the gods — 14 feet tall, blinking in sequence, a radioactive banner for shirts, collars and the blood-and-thread empire beneath it.

Now it sits quietly above the coffee queues and real estate auctions.

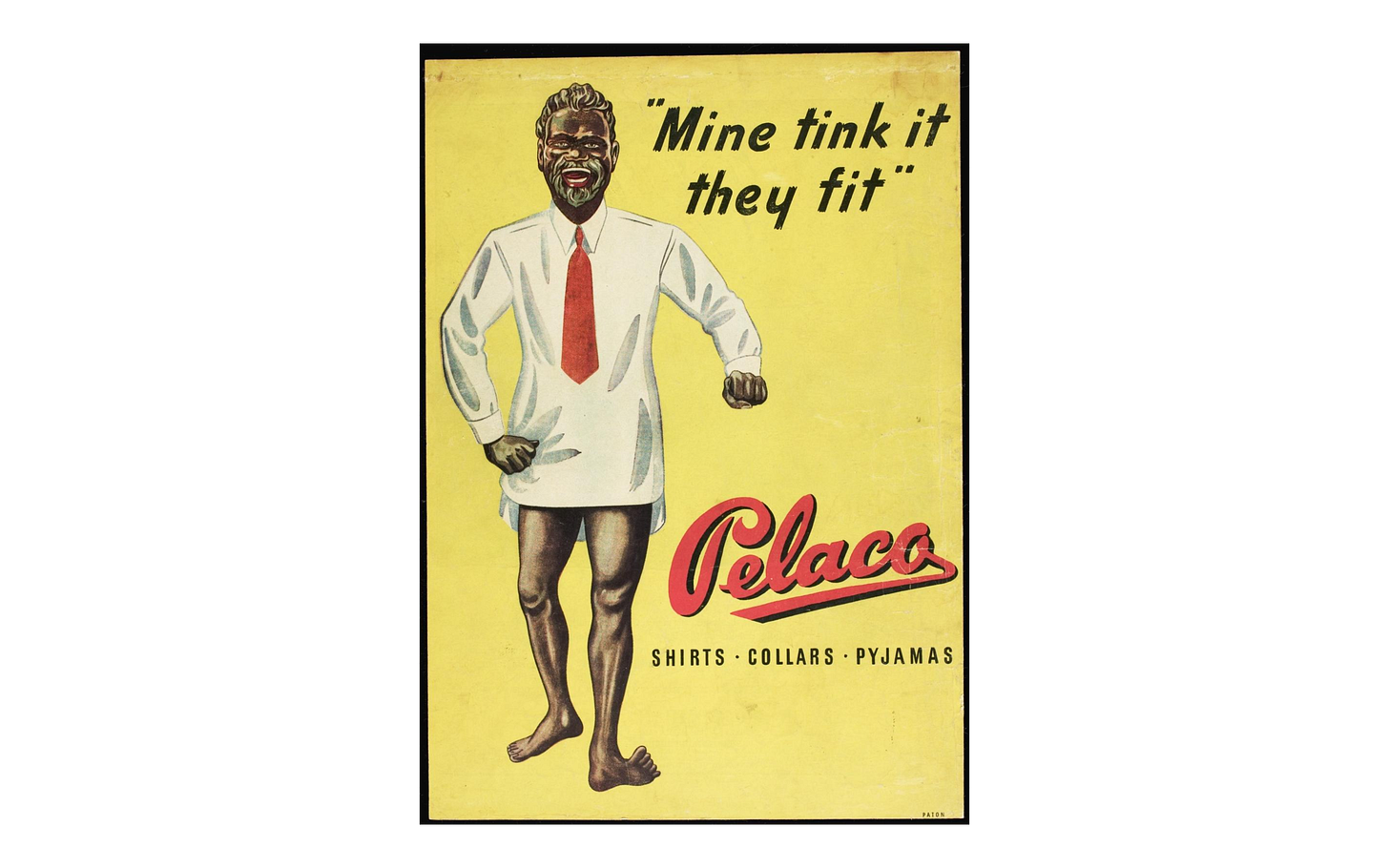

But don’t be fooled. That sign still talks. If you stand beneath it long enough — maybe after a few whiskeys or a week of bad sleep — you’ll start to hear the ghosts. Seamstresses on tea break. Jazz drifting up from the factory floor. A grinning Aboriginal caricature in nothing but a shirt, yelling “Mine tinkit they fit!” into the white void of colonial advertising.

Welcome to Pelaco.

The Shirt Kings of Richmond

Pelaco was stitched together in 1906 by two men — J. K. Pearson and J. L. G. Law — who mashed their surnames into a single word and cranked out white shirts like they were building the British Empire one collar at a time.

By the 1920s—after they’d conquered Gipps Street and Fitzroy—they built a five-acre fortress on Richmond’s Goodwood Street: a four-storey temple to textile capitalism with windows big enough to see your own ambitions leap from the roof.

They hired women — lots of them. By 1926, 800 women stitched their fingers off for Pelaco. By the ’50s, that number hit 1,500 across ten factories. The shirts went national. The collars gleamed like halos. And towering over it all was the sign — that big bastard spelling out P-E-L-A-C-O like the Ten Commandments of cotton.

Dancing and Dagger Work

The top floor was an industrial factory with a pulse: jazz at lunch, a Wertheim piano in the corner, hand-washing stations. You could sew buttons all day, then do the Charleston at lunch. Below, the cutting room ran like a casino — 80-foot tables, 200 folds of fabric laid out, electric knives slicing through it like it owed money.

They were efficiency freaks with a conscience. No Saturday work from 1908. An industrial psychologist on staff by 1928. This wasn’t just a shirt company — it was a social experiment with stitch counters. Piecework pay, sure. Pressure? Absolutely. But if you didn’t pass out, you got a nice shirt at cost.

Pelaco was equal parts pride and propaganda — a machine of industrial optimism humming on the edge of burnout. But if you asked the women who worked there, many of them would’ve said the same thing: Better here than anywhere else. And that’s the trick, isn’t it? Build a gilded cage and make it dance.

Pelaco Bill: The Grin That Sold a Nation

Then there’s Pelaco Bill. Oh boy. Strap in.

From 1911, Pelaco’s ads featured a smiling, pantsless Aboriginal man in a crisp white shirt, speaking in fake pidgin: “Mine Tinkit They Fit.” He was based on Mulga Fred, a real Indigenous rodeo rider from Geelong, which somehow made it worse — as if co-opting a man’s life made the cartoon noble instead of grotesque.

Pelaco Bill was a walking contradiction: a symbol of national pride and casual racism, rolled into one grinning, barefoot mascot. He sold shirts by reinforcing the idea that even the “noble savage” knew a good collar when he saw one.

The image hung around for decades. It became folklore. A marketing fever dream that still shows up in op-shop posters and heritage roundups, long after its cultural expiry date. If there’s a more perfect metaphor for white Australia’s ability to sell itself back its own history — colonised, ironed, and monogrammed — I haven’t seen it.

Rise, Fall, Gentrify, Repeat

By the ’50s, Pelaco was king. By the ’80s, it was obsolete. Shirts were cheaper offshore. Factories were liabilities. The Richmond site was too big, too old, too proud to downsize quietly. So in 1988, Pelaco packed up and moved to Collingwood. Eventually, the company got sold, resold, and shipped out to Maidstone, where it still technically exists in some form.

The building? It’s all media and marketing now. Glass desks and ergonomic chairs where cutting tables used to be. The jazz has been replaced by Spotify playlists. The cafeteria is probably a barista bar with single-origin almond milk. The workers are still mostly women, but the tools are screens, not sewing machines.

And the sign? That hulking neon crown? It refused to die.

After years of neglect, a heritage grant coughed up nearly $400,000 to restore the letters. On June 25, 2016, they were reinstalled — without the neon, but with all the quiet authority of a ghost that won’t lie down.

The Neon Conscience of Melbourne

Now the Pelaco sign is heritage-listed, photographed, Instagrammed, and mostly misunderstood. People know it’s famous, but not why. They see it in Dogs in Space, they name bands after it, they point it out on skyline tours.

But here’s the thing: the sign means something. It’s a relic of a city that made things. It’s a monument to women’s labour, to paternalistic bosses with progress on one side and piecework pay on the other. It’s a racist marketing myth, and a shrine to industrial modernity. It’s where jazz met sewing needles. Where exploitation wore a crisp white shirt and smiled.

It’s been absorbed into the bloodstream. And like all good ghosts, it just waits. Watching the brunch crowd below.

Because the past doesn’t vanish. It flickers.

And the sign still whispers:

Mine tinkit they fit.

Fit what?

Fit everything.

An excerpt from “Symbols of Australia” by Mimmo Cozzolina & Fysh Rutherford:

THEY FIT.

The best known advertising figure in Australia.

In 1906, J. K. Pearson and J. L. G. Law formed a partnership to manufacture shirts. In 1911 they converted it to a company and combined the first two letters of their surnames to create the corporate name: Pe-La-Co.

Mulga Fred, an actual aboriginal from the Geelong area, and the line My tinkit they fit were adopted as the new company's advertising promotion.

Mulga Fred or Pelaco Bill as he became known, was featured on posters, point of sale and in press advertisements. The original portrait of him by A. T. Mockridge, still hangs in the company's head office in Melbourne.

Ken Doe, of Paton Advertising, replaced Mulga Fred with Bambi Shmith and the new advertising slogan It is indeed a lovely shirt sir!

©Mimmo Cozzolino, 1990

Share this post