Here, on the corner of Victoria and Elizabeth Streets in Brunswick, two former grocers lean into the sun like pensioners on a Centrelink pension, soaking up some rays after a lifetime of hard work, meat rations, and mild regret. Their bones are brick. Their breath, neon.

One building wheezes:

SMOKED MEATS. PAPERS. SWEETS.

A flickering gasp from a long-dead milk bar, embalmed in electric tubing.

The other snarls back with fading century-old slogans:

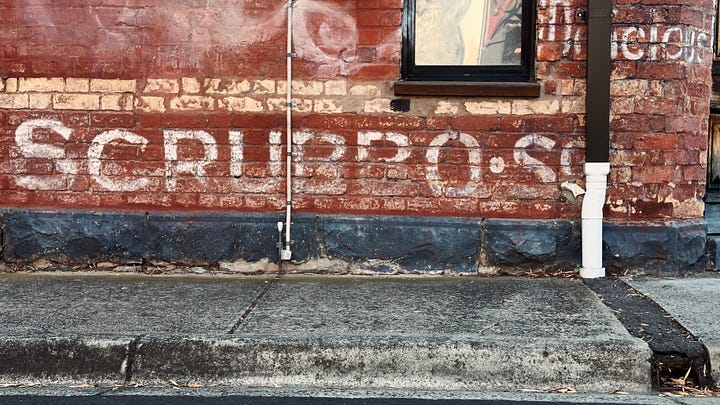

SCRUBBO SOAP.

SEAL TEA IS DELICIOUS.

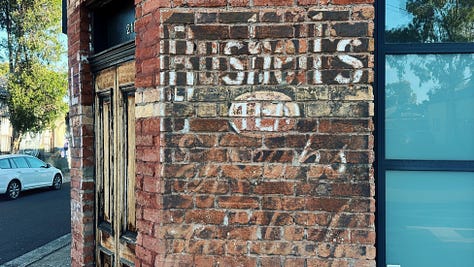

BUSHELLS TEA SPEAKS FOR ITSELF.

Well, it used to.

Back in the 1890s, you couldn’t swing a sack of flour in Brunswick without hitting a corner shop. And in 1895, Thomas Sampson Parkin — grocer, wood and coal merchant, local big shot with a nose for stock and a pair of horses he couldn’t afford to lose — ran both 208 and 210 Victoria Street. His empire was roughly ten paces wide. But illness came, the economy tanked, the horses died, and Parkin’s accounts dried up like day-old bread. By 1896, he was insolvent. The whole shop was sold off, lot by lot, cash on the fall of the hammer.

New names rolled through after that like new bartenders in a cursed pub: John Keane slinging soap and tea at No. 210, while Thomas Egan — later fined for drunk driving a cart down Sydney Road — peddled groceries at the “meats and sweets” building of No. 208. Keane folded by 1915. Egan shuffled next door. The smoked meat shop became a butcher, then a milk bar, now a sun-bleached husk. Time turned them all into footnotes.

But the signs still tell a tale.

Those faded, ancient ads.

Artifacts from an age when groceries weren’t trucked in from orbiting warehouses but made a stone’s throw from the shopfront.

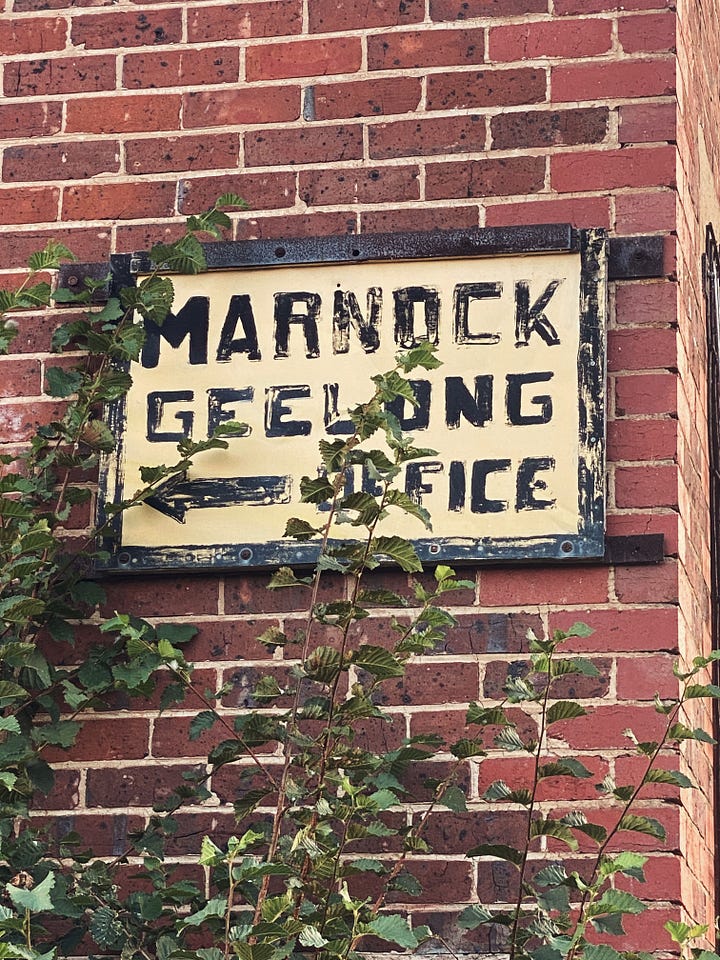

Take Scrubbo — the industrial scouring soap cooked up in a Geelong cauldron before it migrated to Burnley, where its stench of boiled tallow terrorised the neighbours and belched offal into the Yarra.

Or SEAL TEA, a potent brew peddled by John Griffiths and Alfred D. Price — a travelling goods salesman from Omeo and an American expat from Ohio — who wrangled tea leaves, cigars, and cognac under the brand of Price, Griffiths & Co., until the business went up in literal smoke in a warehouse fire and was swallowed whole by a larger booze-and-bulk goods empire.

These shops — and the slogans smeared across them — weren’t just slinging products. They were the local lifelines of a community. They knew your name, your debts, your vices. They didn’t sell lifestyle or brand alignment — they sold smokes and soap and the good tea if you had the coin for it.

And now?

The ghosts still sit there.

Ghosts of local industry, mom-and-pop tenacity, and good old-fashioned entrepreneurial madness — immortalised in plaster and paint. We walk past them daily, squinting at the flaked remains of an empire built on Bushells and broken backs. These are the fossils of working-class Brunswick — not enshrined in glass but fading, weather-beaten, clinging onto the sides of buildings most of us forget to look at.