Otherwise, Yokahama

The outlaw life of Nellie Bong Bew: Gambler, biscuit thief, and the real story of a woman who lived in Melbourne’s shadows on her own terms

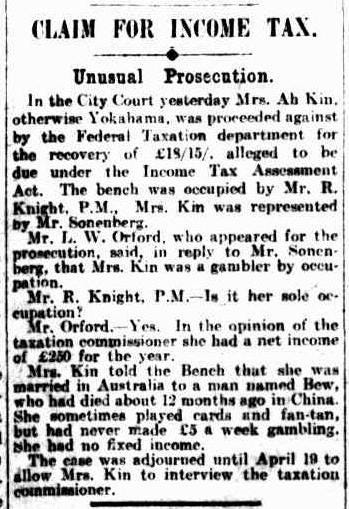

March 16, 1923. A date like any other—except it wasn’t.

The air was thick as Vegemite and twice as difficult to swallow. Somewhere in the bowels of Melbourne’s legal system, a woman stood accused of what every self-respecting Australian was guilty of in one way or another: creative accounting.

To the tax office, she was Mrs. Ah Kim.

To the court, Nellie Bew.

To some, she was otherwise know as Yokohama.

And to the archives, the first name recorded was Tie Cum Ah Chung.

This is a story about a woman who made herself up as she went along.

In a city where men with shiny badges devoted their lives to making sure every number lined up in neat little rows, Nellie was hauled from the back lanes of Little Lon and shoved into the spotlight, accused of skimming £18 in taxes.

The court treated the matter like a royal inquest. Presiding was Magistrate Knight—a man who, if he had ever laughed, had long since forgotten how. The prosecution was led by Mr. L.W. Orford, a man who regarded tax fraud with the gravity of murder.

“She’s a gambler,” Orford declared, scandalised. “She makes £250 a year off it.”

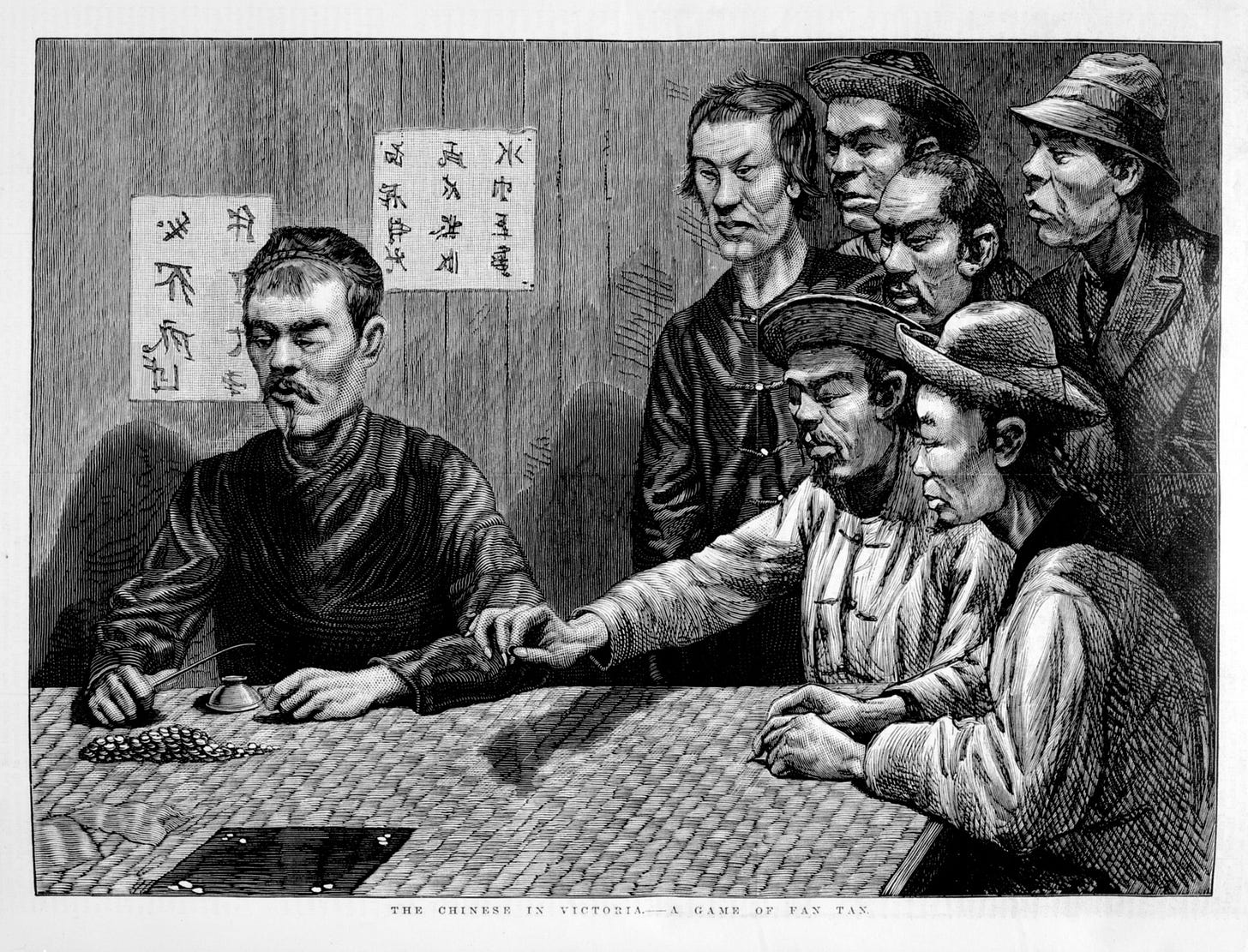

“I gamble, sure,” she said. “I dabble in fan-tan, but I don’t live off it.”

Her late husband, Mr. Bew, had vanished back to China, she claimed, leaving her with the dubious inheritance of widowhood and suspicion on how she kept the lights on. Knight—blinking as if someone had just shouted into his tomb-like courtroom—dismissed the case.

The prosecution slunk away, defeated.

But this was not the first time Nellie Bew had laughed in the face of authority. And it would not be the last.

The Woman Who Wouldn’t Be Pinned Down

Her story is as twisty as the Great Ocean Road and twice as slippery. Piecing it together has been a lesson in patience, obsession, and a touch of madness.

It began with a mugshot. Black and white. Early 1900s. A young Asian woman, hair messy on top of her head, gaze straight at the lens. Her face says: Seriously? This is what life has come to?

Her name is listed as Tie Cum Ah Chung. Her alias: “Yokohama.” Her birthplace: Japan—despite the Chinese name.

Whether it was her own invention or the jailer’s lazy guesswork, her identity was already a tangled mess. A mystery. A puzzle. A provocation.

It pulled me in like a riptide.

Queen of Little Lon

Nellie once lived at 17 Casselden Place—a brick cottage now home to Little Lon Distilling Co., where they brew gin in the heart of what was once Melbourne’s most notorious neighbourhood.

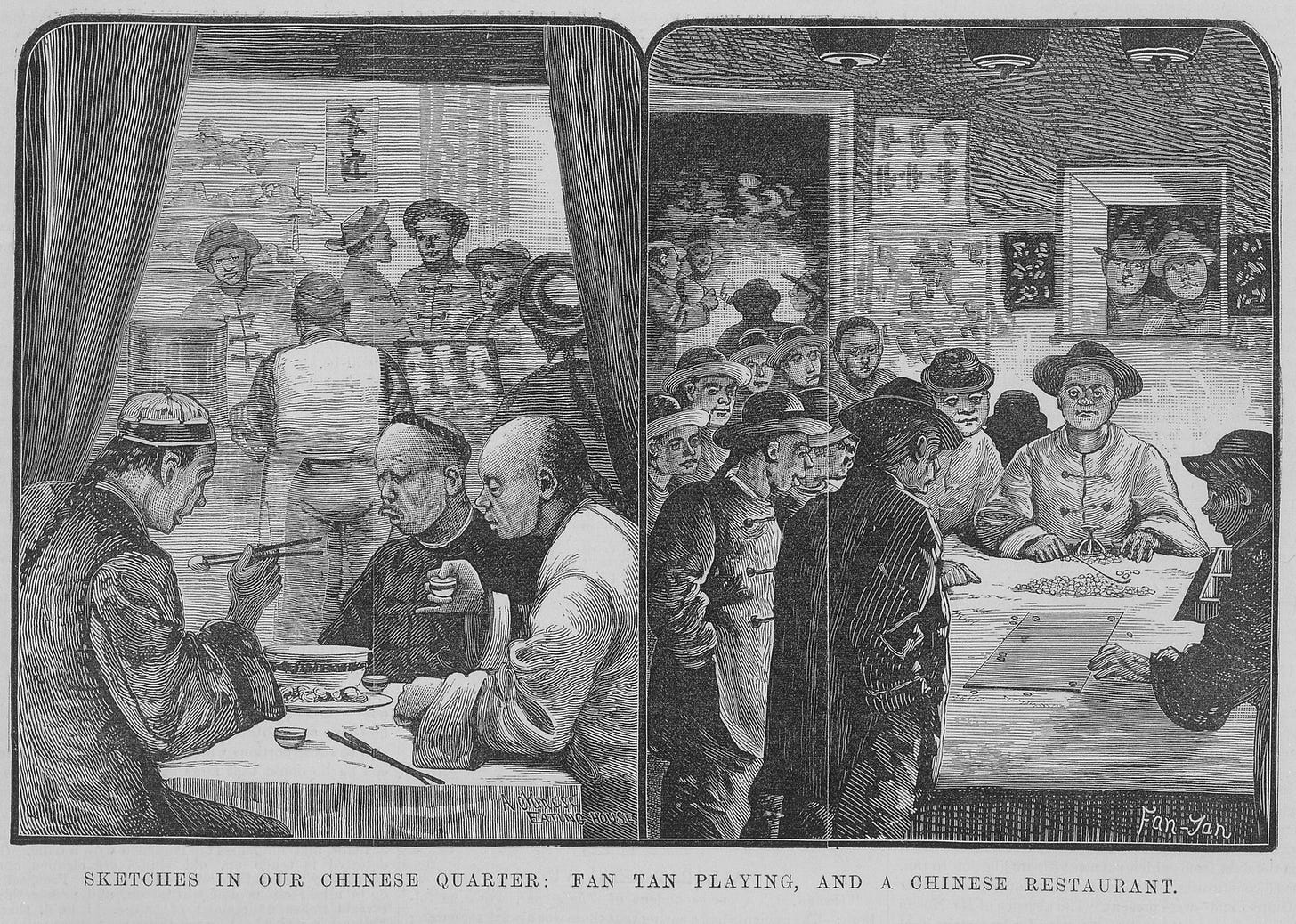

Back then, Little Lon was a warren of narrow laneways slicing through the city’s east end. It was the place respectability went to die. A carnival of sly grog, gambling, opium, and sex work. It was dirty, chaotic, and full of life.

By the 1850s, it had earned a reputation as Melbourne’s shadow city. Sanitation was a joke. Toilets were holes in the ground. Piped water was a pipe dream. Disease, rats, and poverty were part of the wallpaper.

And yet, it pulsed with survival. Immigrants, outcasts, widows and runaways—they made a life there. In the margins. In the mess.

That’s where Nellie thrived.

She lived like a queen in the kingdom of the fallen, carving out her own domain—though what name she ruled under depended on the day.

The Biscuit Heist and the Making of a Fugitive

Nellie Bew wasn’t born Nellie. Before she was the toast of Little Lon—or at least the most wanted—she was Tie Cum Ah Chung, a Chinese teenager living in Hobart, Tasmania, in the early 1900s.

She worked as a domestic servant. She was small—160 centimetres tall—and her face bore the scars of smallpox. A survivor’s face. A fighter’s face.

The world was not especially kind to women like her, nor was it interested in their comfort. She lived on the margins, just close enough to survival to make it inconvenient.

And then, one night in 1903, she got a craving. Maybe for biscuits. Maybe for trouble. Probably both.

It was just after 11pm when she walked into Mrs. Meredith’s shop. She ordered a pound of biscuits. Then another. Then—while the shopkeeper’s back was turned—she grabbed the lot and sprinted out the door like she was chasing freedom.

It was, objectively, a terrible heist.

She was arrested almost immediately.

In a just world, she might’ve been told off, fined, given a slap on the wrist. Instead, she got one month in jail. Then, when she tried to lie her way out of it in court—badly—she got another month for perjury.

That was Australia in the early 20th century: steal a biscuit, lose your freedom.

By 1906, she had made her way to Launceston. Someone had been shot. Tie Cum was a key witness. She gave her statement in fluent English, which shocked the authorities more than the shooting itself.

You have to understand: the newspapers had spent years butchering her name like drunks playing Scrabble. Tie Cum. Ti Cum. Tiecom. Tie Gum. Chinese. Japanese. Sometimes both. Often neither.

And yet, there she was, speaking better English than the men holding the pens.

Her name, her language, her origin—everything about her was slippery, shifting, shapeshifting. She refused to be pinned down.

And that terrified people.

Escape Artist

Some say she was deported. Others say she left by choice. Either way, around 1907, she vanished from Tasmania.

And in 1909, she resurfaced in Rutherglen, Victoria—rebranded.

She married a man named George Bew. On the marriage certificate, she didn’t even write her name. She marked it with an “X”—an old-world signature that said I’m here, but you don’t get to name me.

The papers wouldn’t stop trying. Tie Cum. Yokohama. Mrs. Ah Kim. Nellie Bew.

But her real name, her chosen name, was buried under every assumption they made about who and what she was supposed to be.

Outlaws, Mauds, and the Art of Surviving Respectability

By the 1910s, Nellie Bew had drifted deep into Melbourne’s underworld. At the same time, the papers painted Casselden Place—her future address—as a den of sin. The kind of place the police raided for fun and the press condemned with theatrical disgust. A woman living there had two choices: go invisible, or go infamous.

Nellie chose the latter.

Before settling into Casselden Place, she was arrested in Geelong for “vagrancy”—a catch-all crime that usually meant “existing while poor and female.” That night, she was with two other women, both named Maud. Edwards and Gunter. The Mauds.

Maud Edwards floated through the criminal records without ever quite sticking. A drinker, a frequenter of smoky rooms, someone always seen but rarely caught. Gunter, on the other hand, was infamous. The press had been salivating over her since she was sixteen, when she was found dazed and drooling in a Little Lon opium den.

The three of them—Nellie and the two Mauds—were arrested together for doing what women like them had always done: surviving. Drinking. Laughing. Living just far enough outside the law to be dangerous to the status quo.

Their crime wasn’t theft, or violence, or fraud.

In the eyes of the law, that was unforgivable.

A year later, Nellie was arrested again—this time with May Smith, another woman of the city’s fringes. The charge? “No lawful means of support.”

Translation: the state couldn’t see how they were surviving, so it decided they shouldn’t be.

But Nellie wasn’t just scraping by. She was thriving in the margins. Dancing on the line between poverty and pleasure. Every arrest was a badge. Every fine, a tax for not fitting in.

She didn’t want what respectability had to offer. And even if she did, it wasn’t offering it to women like her.

Especially not women with faces marked by smallpox.

Especially not women who spoke perfect English with a Chinese name.

Especially not women who chose reinvention over obedience.

House of the Fallen—and the Free

As Nellie was living life and getting knocked down for the privelege, the police kept a close eye on 17 Casselden Place.

It was raided repeatedly for sly grog—illegal liquor sold under the counter when drinking was legal but fun wasn’t. One night in 1913, undercover cops crashed a party there. Beer was poured. Laughter flowed. Then the badges came out. Edward Ryan went to jail.

Two weeks later, they raided it again.

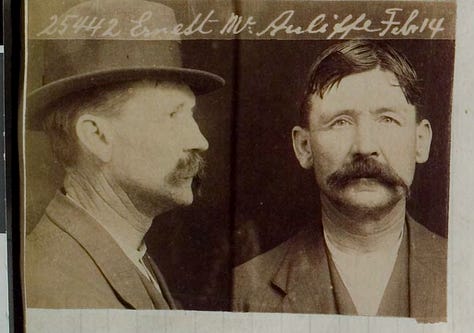

Different faces. Same crime. This time it was Ernest M’Auliffe, alias James Colligan, alias William Lamont—a man with a rap sheet as long as the desperate line at a festival toilet.

Number 17 had become a revolving door for survivors.

Nellie wasn’t always the one caught, but the house became her haunt. A crossroads for the overlooked, the condemned, the people who’d stopped pretending to be anything but themselves.

She lived in a world where European women were banned from bars and betting parlours—but she wasn’t European. And the law, in its narrow-minded efforts to exclude her, had accidentally carved out a kingdom of her own.

Ghosts, Gunshots, and a Final Reinvention

By the 1920s, Nellie Bew had become a fixture of Melbourne’s underworld. A woman of many names and no apologies, drifting between gambling dens, grog houses, and back-alley rooms where the line between survival and crime was mostly theoretical.

She lived in the city’s blind spot.

And Melbourne, ever selective in its memory, tried to pretend she wasn’t there.

The newspapers didn’t. They delighted in her every appearance. A raid. A domino game. A brush with death.

One night in Little Lon, a gunshot rang out. A bullet whistled past her head. The press reported it with glee, treating it like a pulp novel come to life. But this wasn’t fiction. It was just the cost of living in a world that didn’t protect people like her.

Nellie survived, again. Because that’s what she did.

Not quietly. Not cleanly. But on her own terms.

Hearsay, Branding, and the Not-Quite-Truth

Look Nellie up online and you’ll find stories repeated like gospel: that she was a prostitute named Yokohama, that she worked out of 17 Casselden Place for over 15 years, that she jumped ship in Port Melbourne after being “forced” to return home.

It’s a great story. The problem is, I can’t find a single primary source that proves it.

One version, repeated in puff pieces about the current tenants of 17 Casselden—Little Lon Distilling Co.—goes like this:

“Tiecom Ah Chung, or as she was commonly known, Yokohama, was a prostitute of Chinese descent working out of the cottage for over 15 years…” This prostitution story stems from an alleged event where Nellie — by now going by the name “Yokohama” — poured a bucket of water on a man named Charlie Ah Hing as he relieved himself in her garden. In retaliation, Ah Hing supposedly ratted her out as a prostitute to the cops.

It’s quoted widely, even credited to a Melbourne crime historian. But the source? Never cited.

In all my digging—through Trove, police gazettes, death records, court appearances—I have found no evidence Nellie Bew was a sex worker. She may have been. She may not. But the confident assertion that she was, plastered over drink menus and branding collateral, smells more like marketing than history.

It’s a tale too tidy to be true. And like most tidy stories about women who lived outside society’s lines, it tells us more about the people retelling it than the woman herself.

Because when you’re a Chinese woman, living alone, gambling, defying the rules of a city that barely acknowledged you existed, men will call you whatever they want. Especially if it makes the story more salacious. Especially if it sells gin.

Here’s what we do know:

Nellie lived at 17 Casselden Place for a time.

She was arrested for gambling, not prostitution.

She stood up in courtrooms. She outlived her enemies. She made her own name.

The rest? Hearsay. Recycled half-truths. Branding with a ghost’s face.

Nellie doesn’t need a myth to be remembered.

She just needs her story told honestly.

In 1929, she was arrested one last time—caught in the middle of running a domino game during a police raid. The charge? Illegal gambling. The fine? £50, plus £3 in court costs. And, in a final bit of bureaucratic spite, they confiscated £1 from her wallet.

Because the house always wins.

Especially when the house is the state.

That was the last time her name appeared in print.

After that, the trail went quiet.

The End, and Everything It Meant

Nellie Bew died in Fitzroy in 1946. She was 60 years old.

Her death certificate is her final act of resistance. It confirms almost nothing. Her name, her father’s surname—Chung. That’s all.

The rest—where she was really born, who she really was, how she truly saw herself—disappeared like cigarette smoke in a back alley breeze.

What remains is the record of a woman who outran the limits of her time, dodged definition like it was a tax collector, and lived a life most of us wouldn’t have survived.

She crossed oceans. Changed names. Gambled. Lied. Married. Escaped. Hustled. Reappeared.

She made herself up.

Over and over again.

Echoes

A hundred years later, women are still carving out lives in a world that doesn’t always make space for them.

Migrants still shapeshift to survive—tweaking their names, swapping languages mid-sentence, adapting to a society that too often tries to define them before they can define themselves.

And when I think about Nellie—about Tie Cum, Yokohama, Mrs. Ah Kim, the biscuit thief, the sly grog drinker, the survivor—I don’t think of her as lost.

I think of her as familiar.

The Grave, the Flower, the Legacy

In July 2024, I went looking for her grave.

I brought my daughter, Quinn, because history should never be left to the dead. We wandered the paths of Melbourne General Cemetery, past names chiselled deep into marble—names of men who were never arrested for gambling or stealing biscuits but were probably guilty of worse.

We found Nellie in a quiet corner. A simple stone. A name almost worn away.

Nellie Bong Bew.

Just that. No birth date. No epitaph. No hint of the whirlwind of lives lived between the lines. Just a name smoothed by time and indifference.

Quinn placed a single flower at the foot of the grave—because that’s what you do when someone mattered, even if no one else remembers. Especially then.

And in that moment, under a cold sky stitched with clouds, I imagined her—Tie Cum Ah Chung, Nellie Bew, Mrs. Ah Kim, otherwise, Yokohama—standing somewhere just outside the frame of our world, smirking.

Not haunting us.

But reminding us: I was here.

You keep finding these trails in the northeast goldfields right when I've just left them!!

What a fascinating woman though. I can't tell if the immigrant journey has become easier or harder ever since! I strangely love that despite all these travails she had a girl gang to wind up in court with. Good for them.