Take heed, my inquisitive compatriots, as I hurl myself, with a camera in one hand and a shovel in the other, into a tale so drenched in murder, madness and a perverse form of domestic-bliss-turned-nightmare, it could make even the most seasoned of true crime aficionados pause. Brace yourselves, for we are about to embark on a journey that skirts the fringes of sanity, teetering on the edge of a razor-sharp cliff.

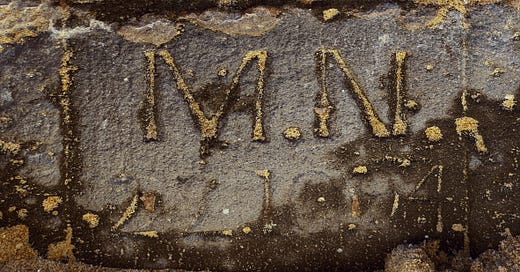

It was a day hotter than Hades after a chilli cook-off, the kind that makes you feel like an ant under God's own magnifying glass. There I was, a wild-eyed treasure hunter in boardshorts, digging through a century's worth of sand and grit on Brighton's sun-kissed shores. I’d gone from cultural archaeologist to bona fide Indiana Jones, searching for a morbid relic from more than a century ago. My prize? A grotesque slab of Old Melbourne Gaol's bluestone wall – a grim marker for a murderer's grave, repurposed as a portion of a 1920s beautification project that doubled as a Depression-era civil works plan.

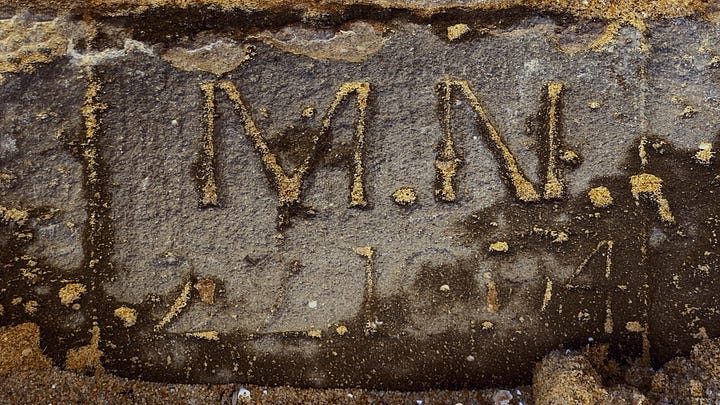

A metre deep into the earth's scorched crust, my fingers brushed against the carved "M. N. 22|10|94" – a ghastly ghost sign from the past buried in time's sandy grave, a whisper of dark deeds and a wretched life snuffed out. But let us spiral back in time to Richmond, 1885, to where Martha Needle, the paragon of motherly affection and wifely duty, nestled into her new home. Her husband, Henry, a carpenter, doing brisk business while Martha doted on their two young daughters. A picturesque, idyllic family portrait. The perfect prelude to an unfolding horror.

This image of domestic harmony was brutally shattered. As the year ended, little Mabel was pushing up daisies. The doc declared it a cerebral tumour, the little girl violently sick and unable to eat. Martha wept for her dearly departed daughter, while Henry, morose, spiralled into a pit of despair, losing his once prosperous job and drifting away from the family like a balloon at a children’s party. Martha was left to bear the burden of caring for their other daughter and their newborn baby girl.

Fast forward four years later, to 1889: Henry, once robust as a redwood, had withered away, gripped by a ferocious fever, his body ravaged by relentless retching, unable to keep any food down. At his deathbed stood Martha, the epitome of wifely devotion, feeding him soup and hot tea. The cause of his untimely demise? A medley of maladies, or so the story went. The doctor was left puzzled why the dying man, in desperate need of nourishment, refused to eat the wholesome meals prepared by his attentive spouse.

A year later, six-year-old Elsie drops dead, supposedly from measles. Seven months on, Martha's youngest, May, joined her sisters in the Needle family’s peculiar parade of death. With one child after another succumbing to mysterious illnesses, I couldn't help but marvel at the sheer audacity of Martha's dance with the reaper, as common as hangovers after a hen’s night. And yet, the "devoted" mother escaped suspicion, all while cloaked in the guise of maternal and wifely virtue.

Now all alone in this woeful world, Martha took the insurance money and had a grand headstone erected to her fallen family. She posted this poem in the pages of The Age:

“I had three little treasures once.

They were my joy and pride.

But one by one they all have gone.

They all have early drooped and died.

All is dark within my dwelling,

Lonely is my heart to-day,

Now unheard, unpitied, unrelieved,

I must bear alone my load of care.

—Inserted by their loving mother.”

Martha's early life had been a tapestry of sorrow, woven with threads of violence: born to an alcoholic mother and living with a step-father who served time for committing unspeakable acts on young Martha. But Martha was a survivor, clawing her way to a semblance of normalcy, only for it to seemingly slip through her fingers like the sand on the shores of Brighton.

Now the scene shifts to Bridge Road, where brothers Otto and Louis Juncken lived above Louis’ saddlery business. Martha, seeking a new beginning, gained employment as their housekeeper and eventual landlady, bringing into their lives her beguiling charm and allure, a plucky widow who was ready to begin anew despite the lousy hand life had dealt her. Martha took to running a small boarding house above the business, the brothers Juncken two of her happy tenants. Otto was bewitched by this winsome widow and, smitten as a kitten, penned her letters dripping with lovesick yearning, fantasising about a shared future. It seemed Martha had stumbled upon a new flame.

But Louis, the more perceptive sibling, sensed something amiss. He had witnessed Martha, fading in and out of fugue states, eerily muttering about searching for her deceased children, sending chills down Louis' spine. Alarmed by this disquieting undercurrent and driven by a growing sense of unease, he forbid the budding romance between his brother and the unstable widow.

As if trapped on a cursed carousel, death once again came around, this time gripping Louis in its icy embrace. Struck down by the same violent vomiting that had taken out Henry Needle’s life years earlier, Louis was cared for til the end by the sibling’s selfless housekeeper. The doctors pronounced the cause of death affliction of the heart, but it was Otto, struck by Cupid’s aimless arrow, who was truly suffering from a case of heartsickness.

In their anguish, the Juncken family dispatched Herman to take over the saddlery business and dissuade his brother Otto from his star-crossed love affair. But in an inexplicable turn of fate, Herman was soon struck by a savage sickness, unable to keep down the dinner and tea prepared by the doting Martha Needle. Herman declined her offer to care for him, instead going to stay with friends. Sensing something rotten in Richmond, his friends urged their fading friend to seek medical intervention. An analysis of Herman’s vomit by government chemist C. R. Blackett revealed the chilling cause of Herman’s illness: arsenic, the preferred poison of domestic murderers in the Victorian age.

A plot was hatched and a trap was laid. Herman, bouncing back from death's door, called on Martha, who insisted on making him a “friendly” cup of tea, despite his insistence that she should steer clear of his brother. As Herman lifted the cup to his lips, the police burst in, nabbing Martha in the act, her kettle brimming with a tainted tea concoction potent enough to drop a bull elephant.

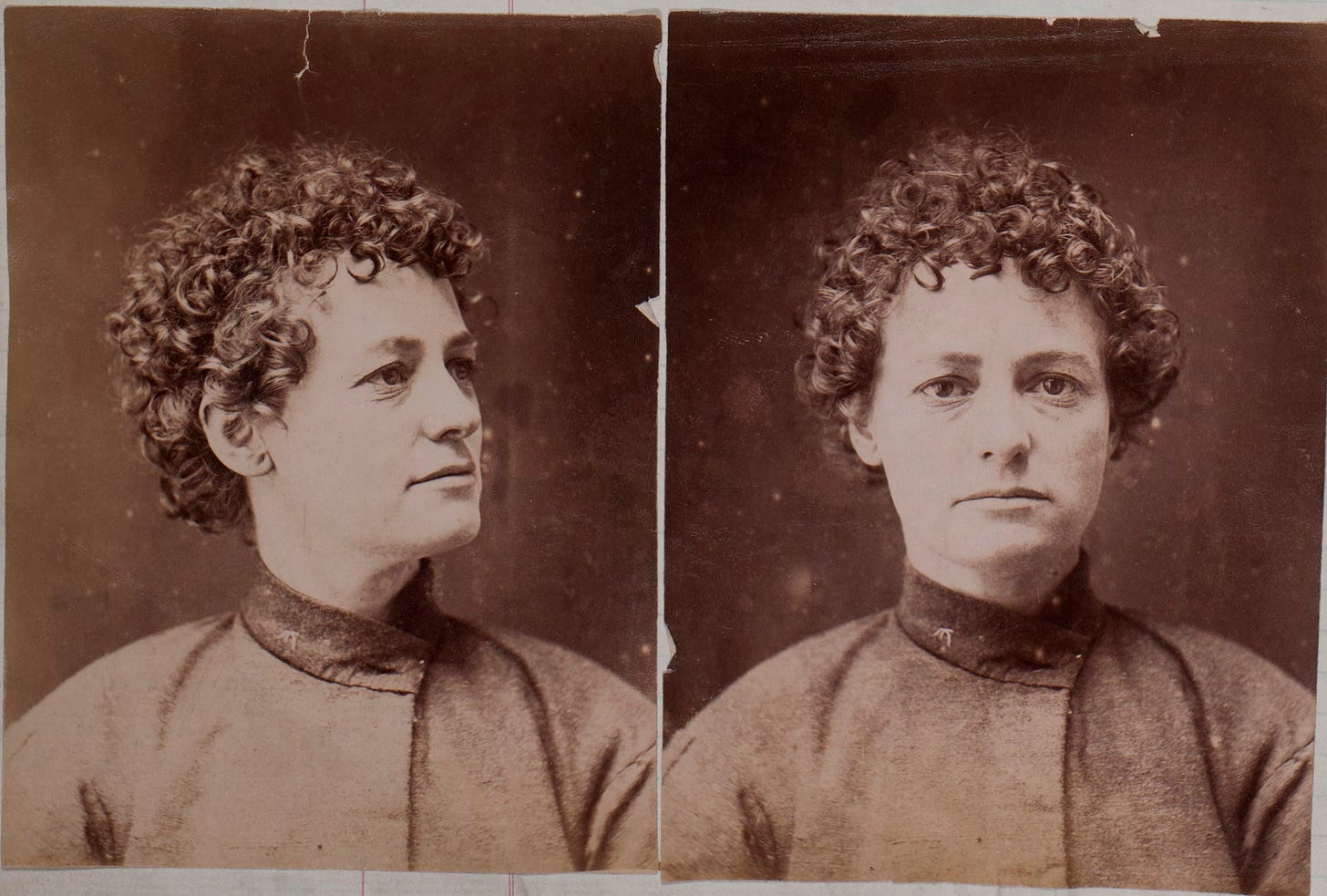

The bodies of Louis, Henry, Elsie and May were exhumed, each found with a bellyful of arsenic. The papers covered every angle, digging up all the dirt and driving the citizens of Melbourne to scream for bloody justice, aghast at the callousness of these heinous crimes. Martha Needle, the arsenic aficionado, seemed to have a knack for dispatching domestic life with a deadly cocktail that would make even the most seasoned mixologist envious. Here was a woman who took 'till death do us part' with a pinch of poison, rather than a grain of salt. She was thrown in the slammer and charged with the murder of Louis. Her trial less a pursuit of truth and more a witch hunt, the public baying for blood like a pack of starved hounds, seeing her not as a woman, but as a spectre of death, draped in the black garb of the reaper.

The courtroom was a circus, the defence’s plea of mental instability met with the judge spouting ‘the law cannot wait while philosophers, physicians and scientists settle metaphysical problems. …Justice must be swift and sure’. The trial was a grotesque performance where justice was overshadowed by the sheer spectacle of Martha's downfall. And there, at the centre of all this lunacy, stood Martha Needle herself, the ringmaster of ruination, her smile a grim slash of defiance as chilling as the poison she so artfully wielded.

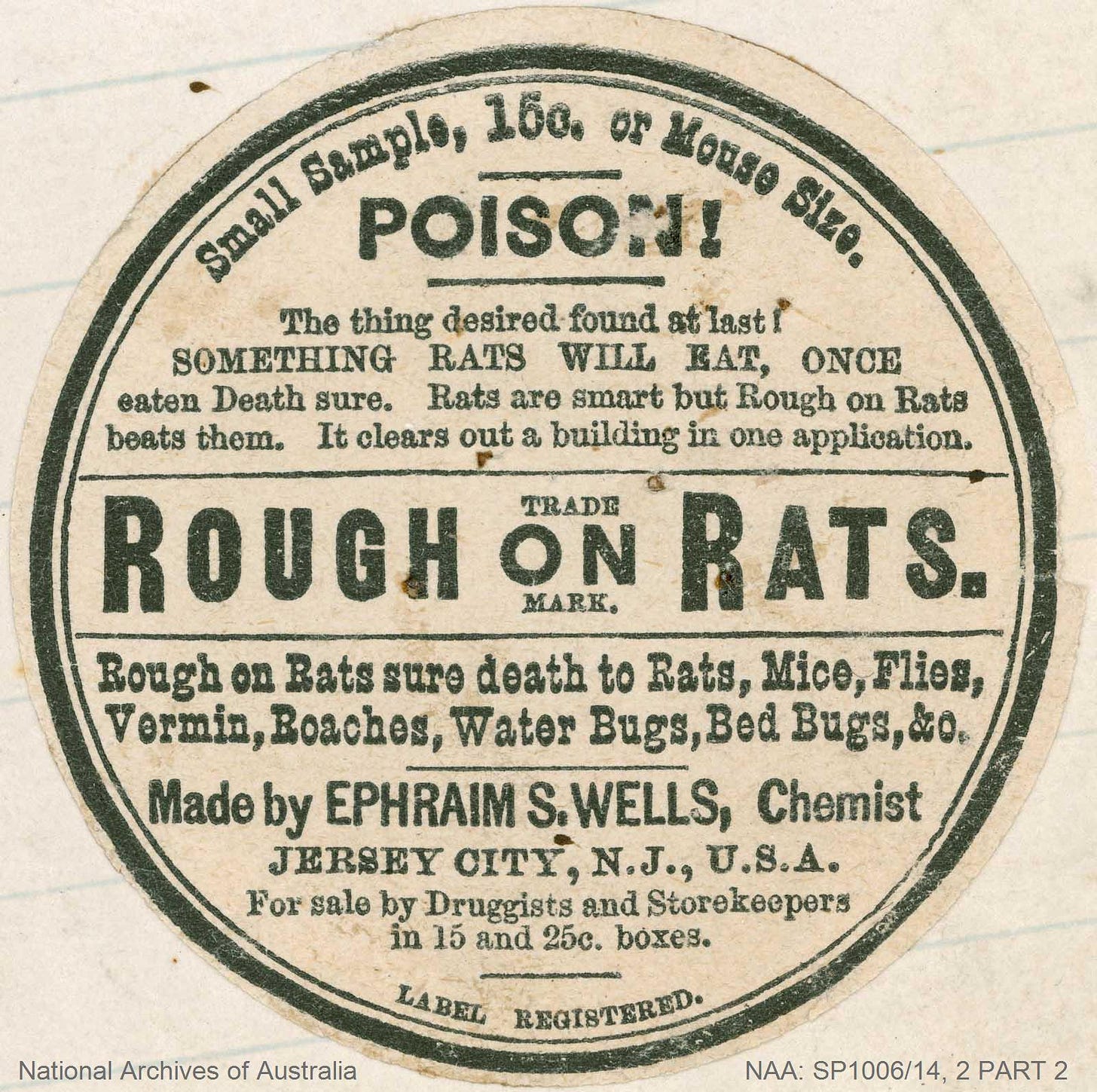

The narrative unfolded with each gruesome discovery and the eventual unmasking of Martha's venomous secret: analyst C. R. Blackett declaring the poison came from a box of Rough On Rats, a 19th century rodent poison that was little more than a box of arsenic coloured with charcoal. The verdict was a foregone conclusion, a crescendo in this symphony of madness. The fall of the gavel echoing like a gunshot, ringing in Martha’s ears as she was declared guilty and sentenced to pay the ultimate price for her homicidal crimes. And through it all, Otto, a madman marooned in the twisted jungle of his own demented heartstrings, inexplicably continued to believe in her innocence.

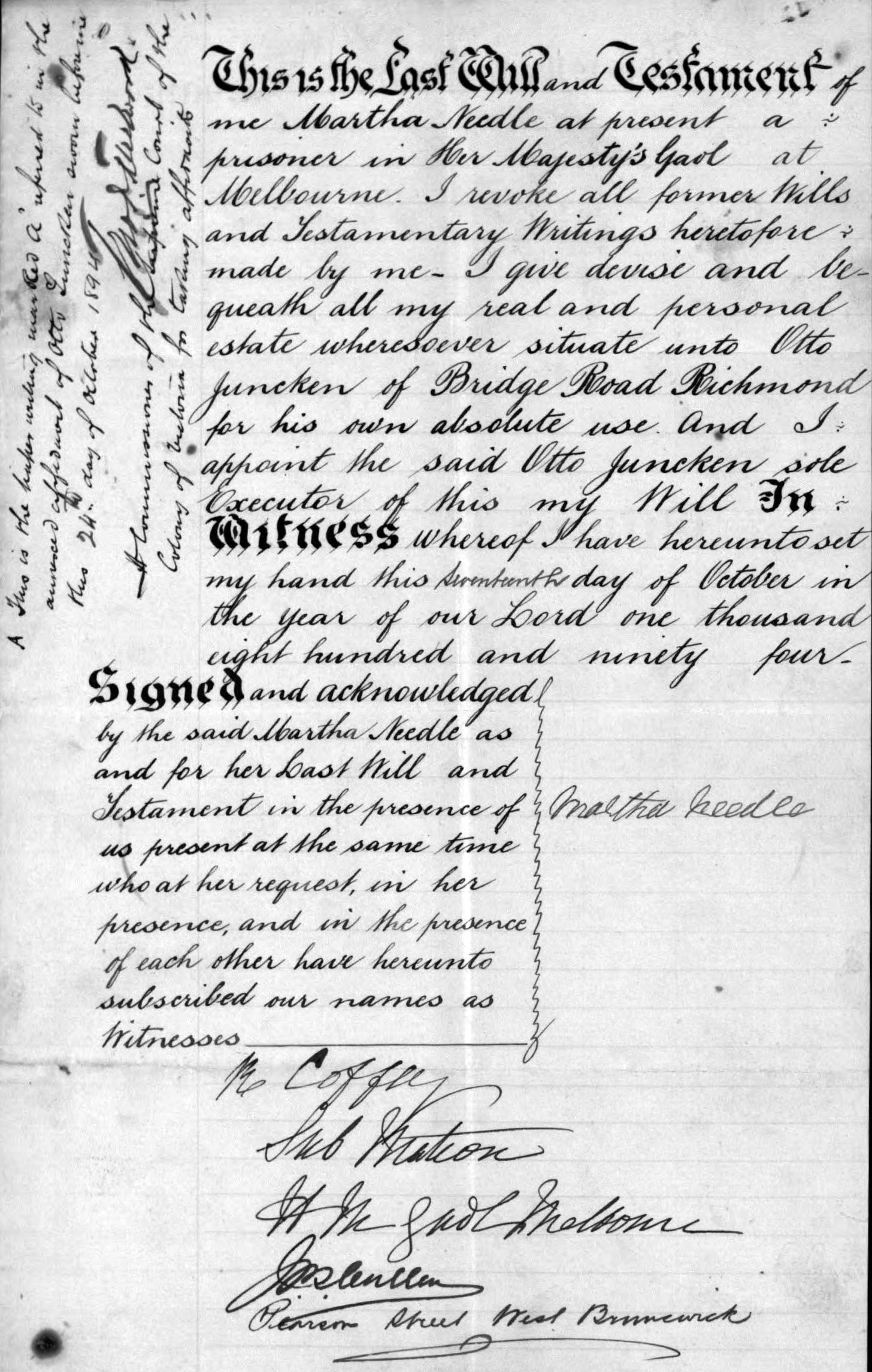

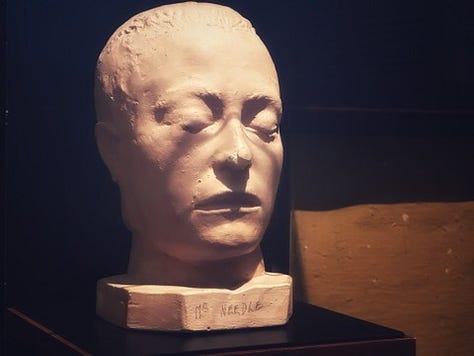

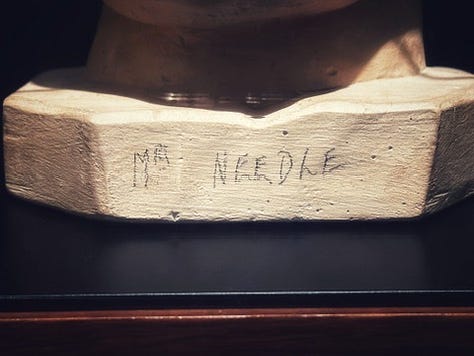

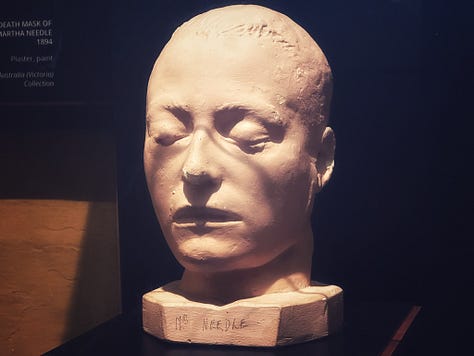

And so, on the 22nd of October, 1894, Martha Needle danced the hangman's jig, a macabre pirouette on the gallows, her legacy sealed not with a kiss but with a cup of poisoned tea. It was the ultimate toast to love and death, served with a side of arsenic-laced irony. Swinging from the noose like a grotesque marionette, the last drop marked the end of the diabolical dame of death. It was her last, chilling performance in a life steeped in duplicity. And in a final act of twisted romance, she bequeathed her earthly belongings to her love-struck puppet, Otto, her final victim, poisoned by love and infatuation.

Martha’s corpse was unceremoniously buried in a crude wooden box in a bleak, barren corner of the Gaol’s grim grounds, later to be uprooted alongside legends of infamy like Ned Kelly, exhumed and transplanted to the somber fields of Pentridge Prison.

The culmination of this ghoulish saga found me, more than a century later, in the sweltering heat of Brighton Beach, digging like a man possessed, in search of Martha's legacy. As I unearthed the stone, I couldn't help but wonder if Martha Needle herself was watching from beyond, amused at the sight of a grown man digging for history's refuse like a dog after a bone. Would she be pleased or pissed I resurrected and then quickly reinterred her forsaken headstone to slumber once again beneath the silent sands? Perhaps she'd offer me a cup of tea for my troubles, a ghastly brew from the great beyond.

In my quest, I had become part of the story, a living example of the enduring allure of the macabre. It was a journey that blurred the lines between past and present, reality and a fever dream. And as I stood there, with the sun setting on Brighton Beach, I realised that in chasing Martha's shadow, I had stumbled into a tale that was as much about the darkness within us all as it was about her.

So here we are, my dear readers, at the end of a chronicle concocted with love, death and one killer tea party. Drink deep from the cup of life, but do take care to check your cuppa first. It could be tainted by the seductive poison of obsession.

Oh, and as a coda to this tale of woe, I should mention Otto Juncken, the starry-eyed fool, married, fathered six children and built a legacy of stone and steel, crafting some of Melbourne's architectural marvels, including the Collingwood Football Club Grandstand and Yarraville’s Sun Theatre. He continued his steadfast belief in Martha's innocence, a testament to love's blinding power, or perhaps, its enduring folly. In his story, we find a reflection of our own lunacies, a cautionary tale of the heart's perilous journey.

Oh wow, that's amazing that Otto built Sun Theatre! I love when these deep dives into unfamiliar territory take us back to all-too-familiar haunts. At least someone came good out of this sorry story. Also, the mystery whether it was indeed Robur - the "good" tea of choice - Martha was serving remains... in my head that's what I'd like to believe!