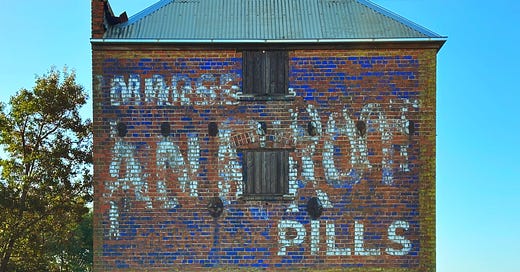

Out past the strip malls and servo stops, beyond where the orchards sprawl and the roads stop pretending to be smooth, there stands a brick monolith: the old chicory kiln of Bacchus Marsh.

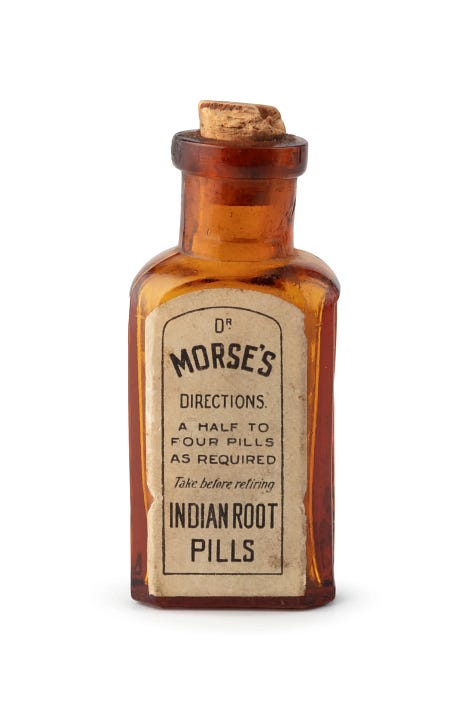

“DR. MORSE’S INDIAN ROOT PILLS — FOR THE LIVER.”

It’s a beauty. A relic from a time when the liver seemed to do all the body’s heavy lifting. And at the heart of it all was T.G. Pearce.

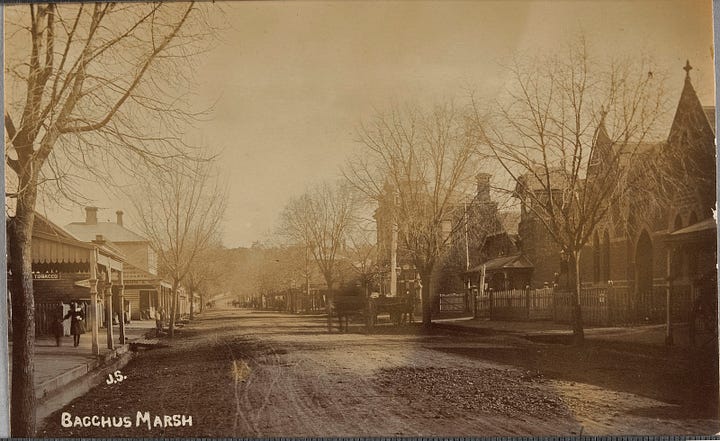

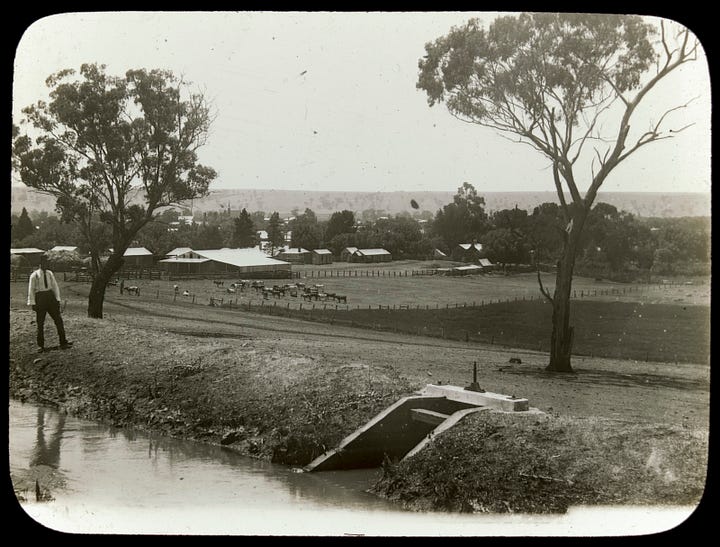

Born in 1853, Thomas George Pearce landed in Australia as a wide-eyed ten-year-old, in a country still figuring out whether it was a prison, a paddock, or both. He grew into a man of many hats—he was a founder of the area’s Baptist church, an irrigation pioneer, amateur photographer, public garden supporter, and relentless tinkerer.

His father, Thomas senior, opened a general store at the still-standing family home in Bacchus Marsh. Like all good colonial enterprises, it sold everything from sugar to seeds, crockery to actual opium. Eventually, T.G. and his brother Ebenezer took over and rebranded it Pearce Bros.—a one-stop emporium for hats, drapery, and miracle cures of dubious legitimacy.

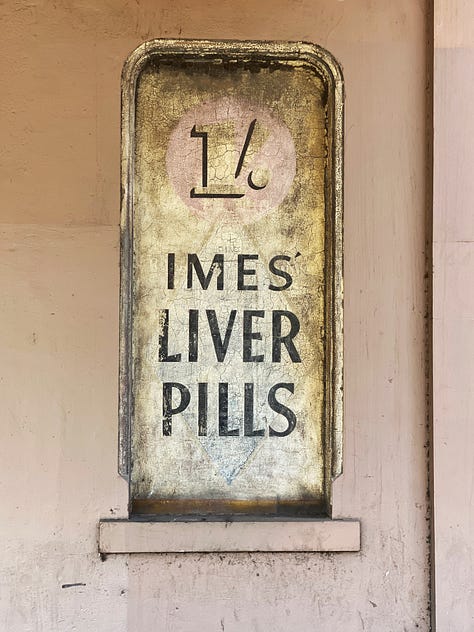

But T.G. didn’t stop at opium and ointments—he also farmed chicory, an earthy, bitter crop used to flavour coffee. He built a kiln to dry it, a brick-and-mortar furnace that still squats proudly on “Pearce’s Paddock”. And right across its front, painted proudly, was an advertisement for his shop’s best-selling product: the miracle of Dr. Morse’s Indian Root Pills—cure-all for every ailment under the Australian sun.

According to the ads, these pills fixed it all: indigestion, blotchy skin, constipation, even questionable morals. But Dr. Morse himself was as real as a friendly tram inspector. He was a Frankenstein myth cooked up by the Comstock family of New York—stitched together with equal parts snake oil, “native” fantasy, and pure, uncut American bullshit.

The Comstock clan created stories that appeared in proto-comic books: stories of the good doctor healing his dying father moments before he kicked the bucket, that he trekked through Asia and Africa on herb-finding pilgrimages, that he found enlightenment with Native Americans on the plains of Kansas.

But that’s all they were: just stories. Marketing. No more real than the liver cures they hawked in newspapers and on the sides of buildings.

The once-secret ingredients of the pills turned out to be fairly common herbs, most of which were used as laxatives.

Still, the public bought them by the fistful. Because when you’re exhausted, broke, and your guts feel like they’ve been cursed by a vengeful god, a miracle pill sounds like a pretty damn good idea.

T.G. Pearce died in 1914, just before the Spanish flu made Dr Morse’s pills a household name throughout Victoria. Ebenezer kept the shop running until 1921, and the kiln slowly crumbled into a footnote. By then, the chicory trade had withered—too much work, not enough payout—and the kiln was already being called “old” in 1913. Time, like a dodgy liver, waits for no one.

Today, the kiln still stands in its field, faded lettering and all, a crumbling monument to colonial commerce, DIY medicine, and the beautiful human knack for believing the unbelievable.

And as long as that sign still clings to the brick—flaked, faded, but still fabulous—it whispers to every passing traveller:

“Your liver’s not fine. But don’t worry — we’ve got something for that.”

An oldie but a goodie! I'm really enjoying these longer-form revisits, great memories of being in place attached to many of them I can hopefully relive soon.