You’ve probably passed it a hundred times.

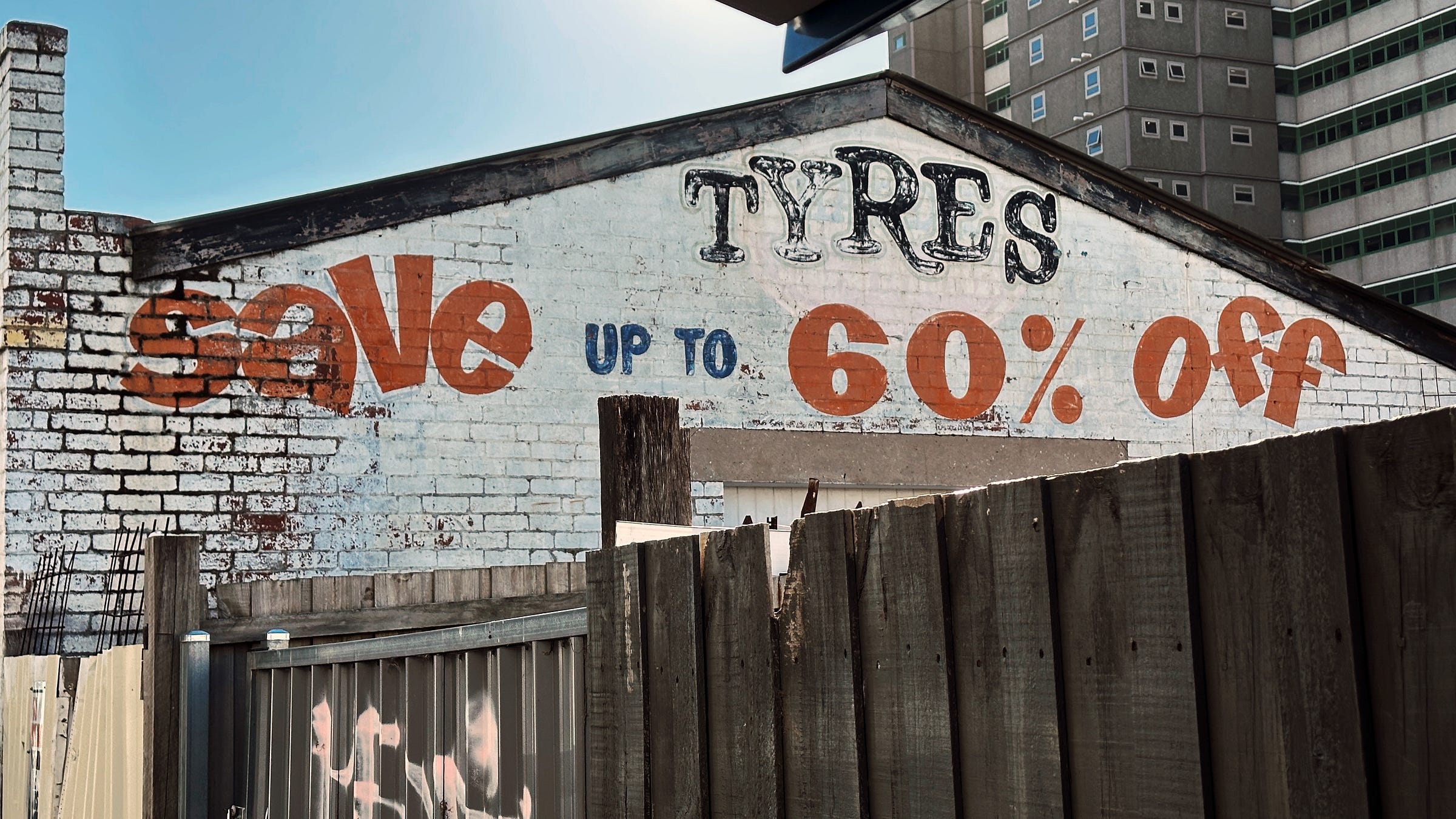

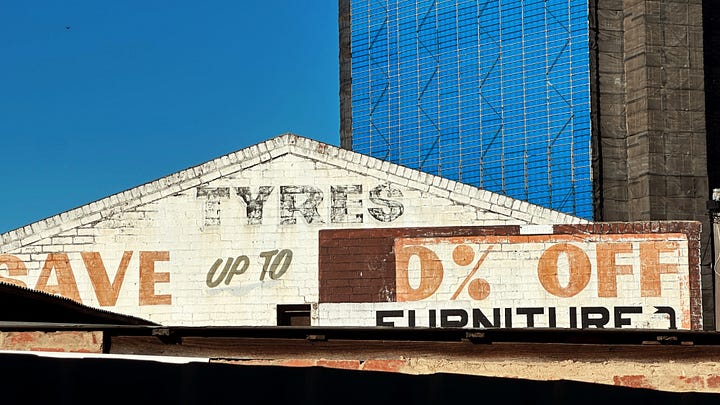

Bright orange typography clinging to the sagging skin of a building on Ascot Vale Road, screaming out a promise from another era:

“TYRES — SAVE UP TO 60% OFF.”

Painted in the bold, vibrating style of a 1960s discount frenzy, it’s a relic from the days when fuel prices were jumping by 25% and drivers scrambled to keep their wheels turning.

But beneath that shouting sign — under layers of enamel, exhaust, and economic transformation — lies the soot-blackened soul of something much older:

The Ascot Shoeing Forge.

From the early twentieth-century up until the 1970s, this building wasn’t selling rubber to commuters. It was a working blacksmith’s forge, hammering steel onto flesh-and-blood horsepower. A place where iron met hoof, and Melbourne’s momentum depended on the men who worked there.

The air was thick with smoke and sweat. The soundtrack wasn’t engines revving — it was the clang of steel on anvil, the sharp exhale of a tethered pony, and the guttural curses of a farrier avoiding a swift kick to the ribs.

An ad from The Age in 1937 says it all:

“FARRIER. Floorman. Must be good. Few days. Waters, Ascot Shoeing Forge.”

It might read like a throwaway job ad, but this was a call for someone who knew the intricacies of hooves and fire. Who could catch a rearing Clydesdale mid-kick and keep hammering with a mouthful of nails and a cigarette behind his ear.

The Ascot Shoeing Forge was part of a thriving equine ecosystem. Flemington, after all, is racing country. Without shoes, even the best-bred mare was just expensive dog food with a pedigree.

For decades, this suburb rang with the sound of forges, stables, and saddlers. But by the 1970s, the Shoeing Forge’s soot-streaked walls were recoated with the shine of the automotive age. The hammer was replaced by the hoist. Enter Marzella Motors — tyre dealers peddling deals on four wheels, always at a discount.

The change wasn’t just cosmetic — it was cultural. One decade, leather aprons and molten iron. The next, moustached mechanics selling steel-belted radials over the phone.

The sign — “Tyres - Save Up To 60% Off” — is in reality a collision of two worlds. A billboard-sized eulogy for the horse-drawn city that once was.

And in many ways, that’s the story of Melbourne.

Before freeways, before parking meters and bumper-to-bumper frustration, Melbourne moved on hooves. Horses hauled everything: carts, cabs, ploughs, funeral processions. And no part of the city felt that rhythm more than Flemington, Kensington, and North Melbourne.

These were neighbourhoods of farriers.

Melbourne may have buried its blacksmiths, but the bones are still there. Every November, when the nation pauses for the Melbourne Cup — gin in one hand, betting slip in the other — you can still hear it in the air: the ghostly clip-clop of hooves in the bluestone streets of Flemington and Kensington.

Next time you pass that battered sign on Ascot Vale Road, the one still shouting about cheap tyres from a long-dead decade — look closer.

This wasn’t always a petrolhead’s paradise.

It was once a forge — a place of fire, sweat, and steel.

Where horses were the engines.

And farriers kept the city moving, one shoe at a time.